Kenny Washington's legacy lives on thanks to efforts of his daughter and others

PostPosted:4 years 9 months ago

https://www.therams.com/news/kenny-wash ... y-lives-on

Kenny Washington's legacy lives on thanks to efforts of his daughter and others

Stu Jackson

STAFF WRITER

Kenny Washington passed away when daughter Karin Washington Cohen was only 15 years old.

Karin said her father didn't talk much about his professional football career when she was growing up, so she had to gather details through other sources.

"Most of the information that I got was from my mother, and from Woody Strode and his son," Karin said in a phone interview with theRams.com last Thursday.

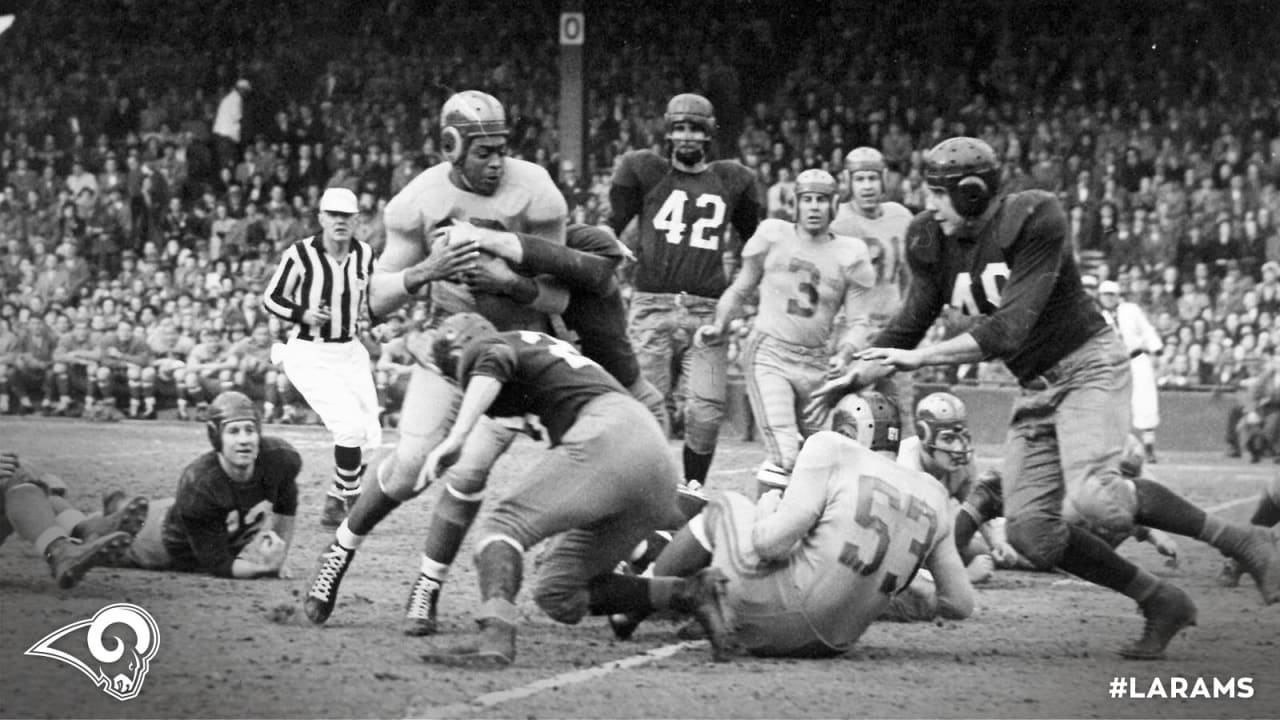

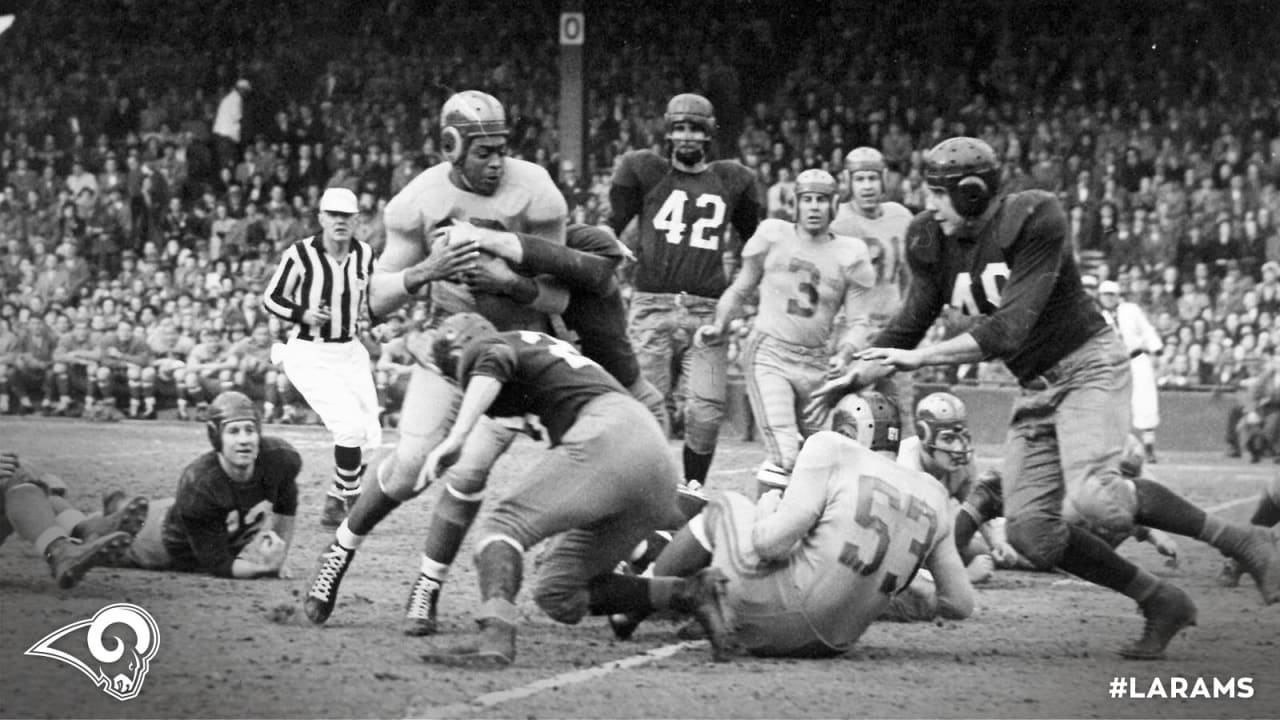

Woody and Kenny, she later learned, broke the NFL's color barrier. The Rams signing Kenny in 1946 ended a 12-year ban on black players in the NFL and made him the first of the league's modern era.

Behind her own contributions and the efforts of others, Karin continues to learn more about – and keep alive – her father's legacy.

Born on August 31, 1918, Kenny Washington grew up in Los Angeles' Lincoln Heights neighborhood. After leading Lincoln High School to a city title as a junior and state championship as a senior, he went on to star at UCLA, where he shared a backfield with Woody Strode and Jackie Robinson.

Although he led the nation in scoring in 1939 and became the first Bruin football player to earn All-America recognition, Washington's professional football options were limited after graduation.

The NFL was midway through a ban on black players that had been pushed by Washington Redskins owner George Preston Marshall. Bears owner George Halas tried to overturn it but was unsuccessful, so Washington joined the Los Angeles Police Department and played four seasons of semi-pro football – two with the Hollywood Bears and two with the San Francisco Clippers – according to a biography published by A&E Television Networks.

It wasn't until the Rams' relocation from Cleveland to Los Angeles seven years later that Washington would get a second chance.

The Rams had their sights on Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as their new home and L.A. Tribune columnist Halley Harding asked if they would consider employing black players, according to a January 2017 story written by Los Angeles Times sports enterprise reporter Nathan Fenno. Allowing a league that excluded black players to use a publicly-owned stadium, Harding contended, was undemocratic. His argument helped create enough pressure to reintegrate the league, which in turn opened the door for the Rams to sign Washington and Strode.

While Cohen learned more about her father through her mother as well as Woody and his son, she still had an idea of the significance at a young age.

"Oh, I knew that when I was around 10. I knew when my father was still alive," Cohen said. "I may not have realized quite the magnitude of it, but I knew what it was. It just wasn't until I got a little older, when I learned more in school, then I realized what the accomplishment was. But I always knew what he done. The magnitude of it kind of grew on me a little bit later."

Civil rights movements in the sixties and high school history classes furthered her understanding, but the stories told by immediate and extended family offered a stunning testament to what Washington endured.

"When (my mother) went to get married, my dad and Uncle Woody were at UCLA and they were in Chicago for a game," Cohen said. "And she talks about having to take the train. She took the train to Chicago. And when she got off, my mother looked white, and I still have the newspaper article, 'Kenny Washington and his negro bride,' because they wanted to be sure that everyone knew he was not marrying a white woman."

Even though Washington and Strode broke the NFL's color barrier, they did not receive the same treatment on the road as they did in Los Angeles.

"I heard this story about how dad and Uncle Woody couldn't stay with the team in a lot of the cities where they were playing – and this is in college as well as when they got to the Rams – and that they would be in the black neighborhood," Cohen said. "Uncle Woody, I remember him telling me how they kind of loved it because they could be out partying, be at the club drinking, doing everything white players couldn't because they had a curfew. But dad and Uncle Woody, they weren't with the team so they could pretty much do whatever they wanted as long as they were ready for the games."

Cohen said she remembered one particular conversation she had with Strode at his home in Glendora, California, when she was around 24, 25 years old and got a lot more information from him about him and her father. Soon, more sources would contribute.

https://www.therams.com/video/kenny-was ... --20366030

Newspaper articles over the following years and an on-camera interview appearance for an NFL special in her 30s continued Cohen's education on her father's legacy.

It extended further many years later, and became known to larger audiences, with another on-camera appearance in the 2011 documentary "Third and Long: The History of African Americans in Pro Football," Johnson McKelvy's 2014 documentary "The Forgotten Four: The History of African Americans in Pro Football 1946-1989," and an interview with Gretchen Atwood for her 2016 book "Lost Champions: Four Men, Two Teams, and the Breaking of Pro Football's Color Line."

"As time went on, there seemed to be more attention paid to him and his role," Cohen said.

Outside of the media, other successful ventures include the Kenny Washington Stadium Foundation restoring Kenny Washington Square in northeast Los Angeles and honoring Washington during the Rams final game at the Coliseum in late December last year, with Cohen and her family in attendance. The league also chose to highlight Washington and Strode's achievement as part of its 100 greatest game changers, coming in at No. 6.

Her efforts, and those of others, won't be slowing down anytime soon. She recalled a recent conversation with a younger friend who originally thought Hall of Fame running back Jim Brown was the first to break the NFL's color barrier.

"(My friend) goes, are you sure he was the first? I thought it was Jim Brown," Cohen said. "And I just looked at him. I said, 'No, I'm sure that he was first.' You see Jim Brown in a football uniform, you see a whole lot of other brown faces on the team with him. I know that wasn't the case when my dad was playing."

Still, just last week she was reminded that there are people who do still remember her father and what he accomplished.

"A lot of black people did a lot of really good things and they don't get recognition for it," Cohen said. "But as recently as yesterday (last Wednesday), I saw a thing on the black history moments on CBS and they talked about my dad two days ago. Yesterday, they were talking about someone else, but on the logo that they are using for Black History Month, on all the pictures, my dad's is one of the pictures. So no matter who they're talking about, when the logo comes up, there's my father. So the fact that all these other people are recognized like that, but he is (there too), he's representing the rest of us, you know? I think it's really good."

Kenny Washington's legacy lives on thanks to efforts of his daughter and others

Stu Jackson

STAFF WRITER

Kenny Washington passed away when daughter Karin Washington Cohen was only 15 years old.

Karin said her father didn't talk much about his professional football career when she was growing up, so she had to gather details through other sources.

"Most of the information that I got was from my mother, and from Woody Strode and his son," Karin said in a phone interview with theRams.com last Thursday.

Woody and Kenny, she later learned, broke the NFL's color barrier. The Rams signing Kenny in 1946 ended a 12-year ban on black players in the NFL and made him the first of the league's modern era.

Behind her own contributions and the efforts of others, Karin continues to learn more about – and keep alive – her father's legacy.

Born on August 31, 1918, Kenny Washington grew up in Los Angeles' Lincoln Heights neighborhood. After leading Lincoln High School to a city title as a junior and state championship as a senior, he went on to star at UCLA, where he shared a backfield with Woody Strode and Jackie Robinson.

Although he led the nation in scoring in 1939 and became the first Bruin football player to earn All-America recognition, Washington's professional football options were limited after graduation.

The NFL was midway through a ban on black players that had been pushed by Washington Redskins owner George Preston Marshall. Bears owner George Halas tried to overturn it but was unsuccessful, so Washington joined the Los Angeles Police Department and played four seasons of semi-pro football – two with the Hollywood Bears and two with the San Francisco Clippers – according to a biography published by A&E Television Networks.

It wasn't until the Rams' relocation from Cleveland to Los Angeles seven years later that Washington would get a second chance.

The Rams had their sights on Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as their new home and L.A. Tribune columnist Halley Harding asked if they would consider employing black players, according to a January 2017 story written by Los Angeles Times sports enterprise reporter Nathan Fenno. Allowing a league that excluded black players to use a publicly-owned stadium, Harding contended, was undemocratic. His argument helped create enough pressure to reintegrate the league, which in turn opened the door for the Rams to sign Washington and Strode.

While Cohen learned more about her father through her mother as well as Woody and his son, she still had an idea of the significance at a young age.

"Oh, I knew that when I was around 10. I knew when my father was still alive," Cohen said. "I may not have realized quite the magnitude of it, but I knew what it was. It just wasn't until I got a little older, when I learned more in school, then I realized what the accomplishment was. But I always knew what he done. The magnitude of it kind of grew on me a little bit later."

Civil rights movements in the sixties and high school history classes furthered her understanding, but the stories told by immediate and extended family offered a stunning testament to what Washington endured.

"When (my mother) went to get married, my dad and Uncle Woody were at UCLA and they were in Chicago for a game," Cohen said. "And she talks about having to take the train. She took the train to Chicago. And when she got off, my mother looked white, and I still have the newspaper article, 'Kenny Washington and his negro bride,' because they wanted to be sure that everyone knew he was not marrying a white woman."

Even though Washington and Strode broke the NFL's color barrier, they did not receive the same treatment on the road as they did in Los Angeles.

"I heard this story about how dad and Uncle Woody couldn't stay with the team in a lot of the cities where they were playing – and this is in college as well as when they got to the Rams – and that they would be in the black neighborhood," Cohen said. "Uncle Woody, I remember him telling me how they kind of loved it because they could be out partying, be at the club drinking, doing everything white players couldn't because they had a curfew. But dad and Uncle Woody, they weren't with the team so they could pretty much do whatever they wanted as long as they were ready for the games."

Cohen said she remembered one particular conversation she had with Strode at his home in Glendora, California, when she was around 24, 25 years old and got a lot more information from him about him and her father. Soon, more sources would contribute.

https://www.therams.com/video/kenny-was ... --20366030

Newspaper articles over the following years and an on-camera interview appearance for an NFL special in her 30s continued Cohen's education on her father's legacy.

It extended further many years later, and became known to larger audiences, with another on-camera appearance in the 2011 documentary "Third and Long: The History of African Americans in Pro Football," Johnson McKelvy's 2014 documentary "The Forgotten Four: The History of African Americans in Pro Football 1946-1989," and an interview with Gretchen Atwood for her 2016 book "Lost Champions: Four Men, Two Teams, and the Breaking of Pro Football's Color Line."

"As time went on, there seemed to be more attention paid to him and his role," Cohen said.

Outside of the media, other successful ventures include the Kenny Washington Stadium Foundation restoring Kenny Washington Square in northeast Los Angeles and honoring Washington during the Rams final game at the Coliseum in late December last year, with Cohen and her family in attendance. The league also chose to highlight Washington and Strode's achievement as part of its 100 greatest game changers, coming in at No. 6.

Her efforts, and those of others, won't be slowing down anytime soon. She recalled a recent conversation with a younger friend who originally thought Hall of Fame running back Jim Brown was the first to break the NFL's color barrier.

"(My friend) goes, are you sure he was the first? I thought it was Jim Brown," Cohen said. "And I just looked at him. I said, 'No, I'm sure that he was first.' You see Jim Brown in a football uniform, you see a whole lot of other brown faces on the team with him. I know that wasn't the case when my dad was playing."

Still, just last week she was reminded that there are people who do still remember her father and what he accomplished.

"A lot of black people did a lot of really good things and they don't get recognition for it," Cohen said. "But as recently as yesterday (last Wednesday), I saw a thing on the black history moments on CBS and they talked about my dad two days ago. Yesterday, they were talking about someone else, but on the logo that they are using for Black History Month, on all the pictures, my dad's is one of the pictures. So no matter who they're talking about, when the logo comes up, there's my father. So the fact that all these other people are recognized like that, but he is (there too), he's representing the rest of us, you know? I think it's really good."